Because the most productive thing I’ve done today is receive a slide rule in the mail and learn how to multiply by pi in a novel way, let’s start with that as the basis for a blog post with which to rectify my sloth.

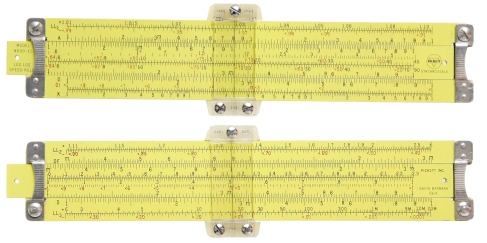

The slide rule I got is a Pickett N600-ES (“eye-saver”, meaning bright yellow) circa 1970 that I won on eBay for about $50. This model is relatively small, made of aluminum and therefore lightweight and durable, displaying a large number of “scales” or number lines with which to calculate. Those are some of the reasons this model was taken to the moon on no less than five Apollo missions, including Apollo 11 (Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin both carried this very model) and Apollo 13, where, I trust, it served them well. And yes, those are some of the reasons I, in turn, bought this compact beauty.

Figure 1. Ceci n’est pas Buzz Aldrin’s actual fucking slide rule, man!

***

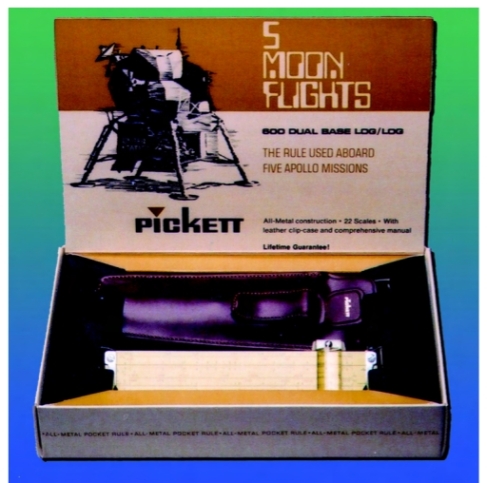

Figure 2. What the box for Buzz Aldrin’s slide rule would have looked like if he had lost the first one and bought a replacement a few years later out of his own pocket.

My slide-rule bender goes back only a month or so, but once I get interested in something, it’s hard to deflect me. First, I posted my top five personal retrocomputing desiderata, and then was intrigued when my friend Zenoli did the same and one of his was a decent slide rule of some kind.

Next, there was a long, unrelated thread about slide rules on the TRS-80 Model 100 list, a list which occasionally veers into other retrocomputing topics. It amused me that people were talking about whipping out their big ten-inch to impress younger engineers (I paraphrase, but only slightly), completely unironically. (Alas, I can only whip out six inches. Before today, I couldn’t even do that.)

Finally, one evening during some documentation builds at work, I started googling about, looking for slide rule manufacturers, and was astonished to discover that there are in some important senses literally none at present. I mean, not even for homeschoolers? I’m not being sarcastic; using a slide rule will improve your numeracy in ways that using a calculator or calculator app never will. It’s a mentat skill.

This is all we have: A few years ago ThinkGeek did manufacture one as a novelty, but the quality was poor and the experiment was not repeated. There is also a Japanese company called Concise that still manufactures special-purpose circular slide rules. And that’s it.

But they can hardly replace the little plastic slipstick my uncle gave me and taught me how to use when I was 10 (he worked at Boeing and had probably just gotten a calculator). For nostalgia is what this quixotic retropursuit is all about, no? (Not quite; see below.) Then, too, my wife Marty’s late father had one, and she thinks it’s here in the garage somewhere… Well, wish us luck with that.

While googling, I learned about the talismanic lunar magic of the N600-ES, and what a solid little performer it is generally, so I sniped one on eBay that was firing in a couple days. And now it’s mine. For me, that’s part of the “great” part of “great and terrible”.

What’s the “terrible” part? We built the Hoover Dam, the Empire State Building, and to a large extent, the Apollo program and its precursors with slide rules. That’s pretty badass, don’t you agree?

“Once and Future,” the “future” part

I assume I don’t need to explain the “once” part…

If you don’t want to buy an N600-ES yourself — or any other kind of slide rule — there are all kinds of “modern-day fun” (as the Retrobits Podcast says) to be had without one. For example, you can play with an N600-ES “virtual slide rule” emulator online or on your Android. There are virtual slide rules for iOS. too. In fact, there are a huge number of slide rule emulators available online and off, not just of my model.

Another bit of modern-day slide rule fun is the UltraLog, a slide rule that was scrupulously designed a couple of years ago by Zvi Doron (who is now deceased) but which was never built. The UltraLog was meant to be the slide-rule fan’s slide rule, about a foot and a half long with 40 well-chosen and ergonomically-presented scales (mine has about 20, and that’s considered a lot; the model Einstein and von Braun used had only nine). There were incipient plans for an independently-funded production run of 500; this is the kind of thing destined for success on Kickstarter, but perhaps Zvi wasn’t familiar with that business model. It might even succeed today. In any case, there seem to be high-quality digital graphics of the UltraLog available; why can’t there be an online UltraLog emulator, at least? (I’ll get right on it.)

There is, by the way, a really good course for learning how to use slide rules at the online International Slide Rule Museum, but it won’t give you much theory. If you want to learn why a slide rule works as well as how, I highly recommend Isaac Asimov‘s lucid 1965 book An Easy Introduction to the Slide Rule, available as a PDF, also at the Museum, or as a used pbook for extortionate prices from your friendly online bookseller.

The gaming/retrocomputing connection

So why am I obsessed with slide rules, and retrocomputing generally?

I’m writing a dictionary of imaginary games notionally published on the equally imaginary planet Glob. A few days ago, I was musing about the games with slide rules there, where they can calculate with things other than numbers, such as days of the week, months of the year, and planets of the solar system. (Yes, I figured out how to do this; my book is “design fiction”, so every game in it is possible to implement in theory. I hope people do, in fact, after the book is published.)

It was then I understood the reason why all this time that I’ve been sketching imaginary games, I’ve also been busy sketching imaginary retrocomputers: machines that still boot into Lisp or Forth, “writer’s notebook” computers with the “cinematic form factor” similar to the Model 100 but with higher resolution, and so on. The people of Glob are my people, as the Elves are Tolkien’s, and they share my aesthetics, as the Elves share Tolkien’s. And I like elegant things.

I am no fan of the board games Advanced Squad Leader or Star Fleet Battles; I can barely comprehend (com-prehend, “togethergrasp”) in my mind the 30-page rulebook to Elder Sign, let alone its big sib Arkham Horror — or, I flatter myself, I don’t care to. The most fun I had at game night recently was playing Nonesuch, a simple trick-taking game for the Decktet that nevertheless offers plenty of emergent complexity. I enjoy the complex, rather than the complicated. I enjoy things I can “grasp together” in my mind and turn from side to side to see, yet which still surprise me — whether they be card games, computer games, or computers.

Returning to computers, I had to install one of the smaller versions of Microsoft Visual Studio at work the other day. Do you know how big the install was? Over seven gigabytes. Do you know how big all of the firmware native to my 1987 Tandy 102 laptop is, including all the applications, and the operating system, such as it is? 32 kilobytes. Does Visual Studio do more than my Tandy 102? Sure, a lot more. Does it do five orders of magnitude more? Does it have 221,000 times more functionality? I’ve been using the previous version for most of a year, and I assure you it does not. (Don’t accuse me of Microsoft-bashing; Microsoft also wrote the Model 100 / Tandy 102 firmware I appreciate back in 1982. Famously, it’s the last code Bill Gates ever touched.) I like elegant computers too, and often that means retrocomputers.

So for games, give me chess variants, games with slide rules, and ten-dimensional card game systems that are nevertheless less complicated than Dominion. For computers, give me the Model 100 and its kin, not Visual Studio.

This is largely the origin of my retrofascination.

Model Mmm

If you have noticed that this post is longer than usual, it may be because I have been writing it on an item from my retrocomputing wishlist: a Model M keyboard, specifically a brand-new Unicomp Ultra Classic USB keyboard. After years of using a netbook as my main computer, I had forgotten until my Tandy 102 how sweet it can be to write on a real computer keyboard, and they don’t come much realer or sweeter than the Model M.

Conclusion

So that’s one item (plus a slide rule bonus) off my wishlist, and four to go. I may give up on the Jupiter Ace, though, because the FIGnition kit, modeled in some ways on the Ace, is so much more available, and I stand to learn much by building one.

Finally, for more information about slide rules than you probably care to know — but it’s curated! — let me direct you to my slide rule bookmarks on Pinboard.